Soap

One substance everyone uses every day is soap, whether it be for washing our hands using a bar of soap,

doing the laundry or washing the floor with detergent. Technically, soaps are ionic compounds from fatty

acids and they are used for a variety of cleaning purposes. Soaps allow particles that cannot usually be

dissolved in water to be soluble and then be washed away. Although made in a different way, synthetic

detergents operate in a similar fashion.

The human skin is under daily attack from various things, such as scorching sun, drying winds, biting

cold weather, bacteria and dirt, and so our distant ancestors learned quickly that preserving the health

of skin is a way for better and longer life. Popular in different civilisations, the benefits of soap

finally managed to appeal to a wide European population in the 17th century, and, since then, the

tradition of maintaining high personal hygiene has experienced only constant growth. With its ability to

clean people's clothes and disinfect their surroundings from harmful bacteria and dirt, soaps remain one

of the most useful and fundamental hygiene tools that mankind ever created.

The first concrete evidence we have of a soap-like substance is dated around 2800 BC. The first soap

makers were Babylonians, Mesopotamians, Egyptians, as well as the ancient Greeks and Romans. All of them

made soap by mixing fat, oils and salts. Soap was not made and used for bathing and personal hygiene,

but was rather produced for cleaning cooking utensils or goods or was used for medicinal purposes.

According to Roman legend, their natural soap was first discovered near a mount called 'Sapo', where

animals were sacrificed. Rain used to wash the fat from sacrificed animals along with wood ashes into

the River Tiber, where the women who were washing clothes in it found the mixture made their washing

easier. It is a nice story, but unfortunately there is no such place on record and no evidence for the

mythical story.

Soaps today come in three principal forms: bars, powders and liquids. Some liquid products are so viscous

that they are gels. Raw materials are chosen according to many criteria, including their human and

environmental safety, cost, compatibility with other ingredients, and the desired form and performance

characteristics of the finished product. In ancient times, soap was made from animal fats and wood

ashes. Today, it is still produced from vegetable or animal fats and alkali. The main sources of fats

are beef and mutton tallow, while palm, coconut and palm kernel oils are the principal oils.

In the early beginnings of soap making, it was an exclusive technique used by small groups of soap

makers. The demand for early soap was high, but it was very expensive and there was a monopoly on soap

production in many areas. Over time, recipes for soap making became more widely known, but soap was

still expensive.

Modern soap was made by the batch kettle boiling method until shortly after World War II, when continuous

processes were developed. Continuous processes are preferred today, because of their flexibility, speed

and economics. The first part of the manufacturing process is to heat the raw materials to remove

impurities. This is followed by saponification, which involves adding a powerful alkali to the heated

raw materials. This releases the fatty acids (known as 'neat soap') that are the basis of the soap and a

valuable by-product, glycerine. The glycerine is recovered by chemical treatment, followed by

evaporation and refining. Refined glycerine is an important industrial material used in foods,

cosmetics, drugs and many other products. The next processing for the soap is vacuum spray drying to

convert the neat soap into dry soap pellets. The moisture content of the pellets will be determined by

the desired characteristics of the soap bar. In the final processing step, the dry soap pellets pass

through a bar soap finishing line. The first unit in the line is a mixer, called an amalgamator, in

which the soap pellets are blended together with fragrance, shades and all other ingredients. The

mixture is then homogenised and refined through rolling mills and refining plodders to achieve thorough

blending and a uniform texture. Finally, the mixture is cut into bar-size units and stamped into its

final shape in a soap press.

The history of liquid soaps and gels started only recently, when the technological and chemical

advancements of the modern age enabled countless inventors to start experimenting with more complicated

recipes. The first appearance of liquid soap happened in the mid 1800's with the exploits of several

inventors. In 1865, William Shepphard patented liquid soap, however, popularity of this product would

not arrive until the creation of Palmolive soap in 1898 by B.J. Johnson.

Advancements in modern chemistry enabled the creation of shower gel. The main difference between liquid

soaps and shower gels is that gels do not contain saponified oil. They are based mostly on petroleum,

have numerous chemical ingredients that help the easier cleaning of skin, lather better in hard water

areas, do not leave a residue on the skin and bathtub, and are in a balanced PH state, so that they do

not cause skin irritations. Because some shower gels can cause drying up of the skin after use, many

manufacturers insert various moisturisers into their recipes. Some use menthol, an ingredient that gives

skin a sensation of coldness and freshness.

The Sun: Our Nearest Star

The Sun is our nearest star and it dominates our sky from a distance of 'only' 150 million kilometres.

Even though it appears to be the same size as the full Moon, it is over 400,000 times brighter, and

dictates when we have night and day here on Earth. The Sun is the largest body in the Solar System and

it is also the most massive, containing 99.9 per cent of the total mass of all the planets, moons, dwarf

planets, asteroids and comets combined. This concentration of mass, and the accompanying gravitational

force, is why the Sun sits at the very centre of the Solar System, pulling all the other bodies in orbit

around it. We are entirely dependent on the Sun for the habitability of our planet, as it provides us

with the energy in the form of heat and light that we require to survive. But it also brings many

potential hazards, from the continual flow of hazardous radiation that always lurks just beyond Earth's

atmosphere, to the sporadic and violent space weather that threatens much of our society's

infrastructure.

Given that the Sun has a volume that is over a million times that of the Earth, yet contains only 330,000

times the mass, we can immediately deduce that its average density is far lower than that of a

terrestrial planet. Indeed, the average density is about the same as that of water, and less than a

quarter of the density of the Earth. The Sun is made mainly of the lightest elements, hydrogen (the

Sun's fuel) and helium, in a gaseous form.

The source of the Sun's energy remained a mystery until Einstein's 1905 special theory of relativity

highlighted the promise of efficient nuclear fusion. For nuclear fusion to occur, matter needs to be

under conditions of tremendous pressure and of extreme heat, so that the electric repulsion can be

overcome, and the nuclei get close enough to smash into each other. It was the English astronomer Sir

Arthur Eddington who realised in the 1920's that the physical conditions within the core of the Sun were

extreme enough to permit the necessary nuclear reactions. The Sun converts 600,000 million kilograms of

hydrogen to helium every second to sustain its phenomenal energy output.

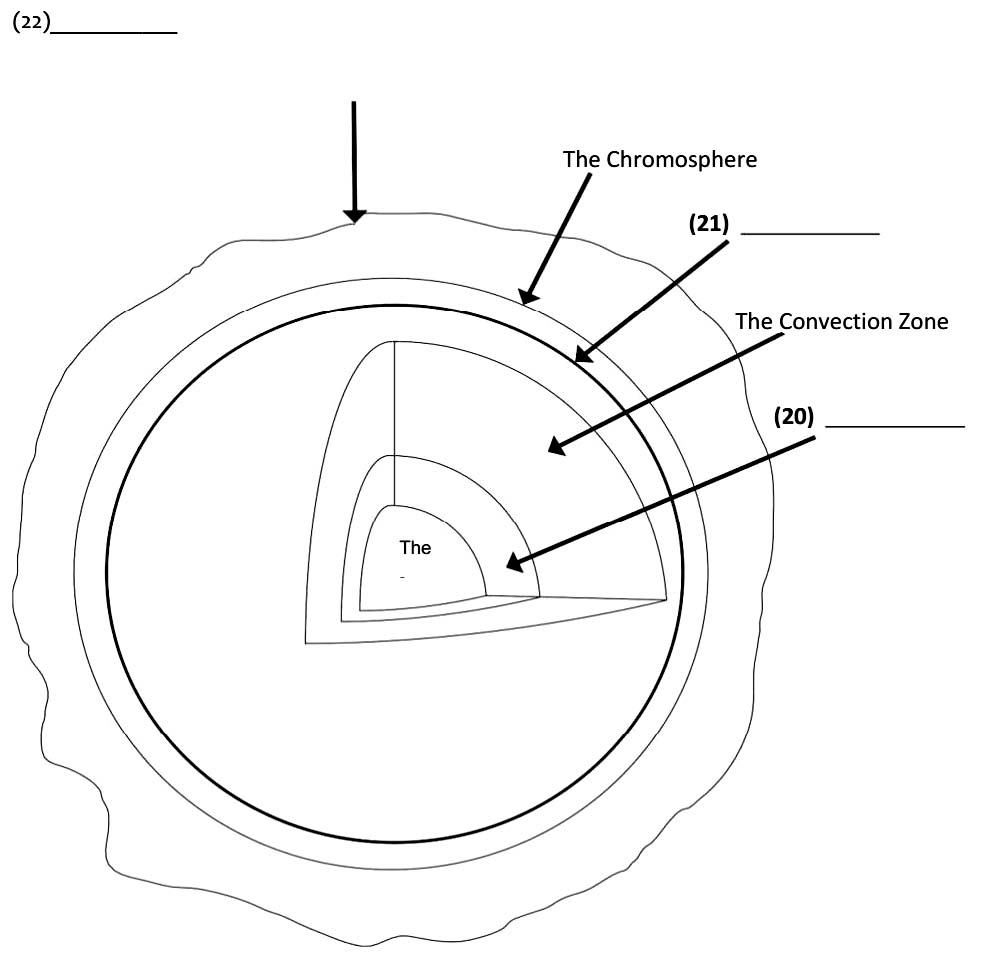

The Sun's core is approximately 15,000,000 degrees Celsius and is the site of the nuclear fusion. The

energy from the core travels outwards through the radiation zone by the transfer of the energy from one

molecule to another. Heated gases move the energy from the radiation zone through to the convection

zone, where the gases start to cool and this causes them to sink back down to the radiation zone.

Outside the convection zone is the photosphere, which is approximately 500 kilometres thick and is the

surface layer of the sun. Beyond, there is a thin layer of gas that surrounds the photosphere called the

chromosphere. Finally, the corona is another layer of gas that extends a long way outside of the

Sun.

Observations of more evolved objects around us in the galaxy lead to our understanding of the eventual

fate of the Sun. The Sun has sufficient hydrogen at the right temperature and density to continue

creating helium for a further six billion years. Then, the supply of fuel, and all possibility of future

nuclear reactions, will eventually be exhausted. By this point, the Sun will appear very different from

how it does today. It will have become a red giant; a much cooler, redder and far more bloated version

of itself, with an atmosphere puffed so large as to swallow up the planets Mercury and Venus and make

conditions pretty uncomfortable on Earth. Eventually, the outer envelope of the red giant will be lost,

expanding away to form a planetary nebula. The remaining hot core of the star will be left exposed as a

white dwarf, which will slowly cool and fade over billions of years, until finally fading into a cold,

dark and dense ball of compressed matter.

From time to time, there are eruptions of matter from the Sun. The magnetic energy in an exceptionally

powerful sun flare can heat and speed up a huge cloud of charged particles to form a coronal mass

ejection. The cloud produced by such an eruption escapes away out into interplanetary space, but can

cause concern if directed towards Earth. When a coronal mass ejection reaches the Earth, it rattles the

Earth's magnetic field to generate what is known as a 'geomagnetic storm'. The occurrence of the flare

gives us advance notice of this event and that it will arrive between 15 hours and a couple of days

later, depending on how fast it's moving, and how clear the passage between Sun and Earth is. The major

effect for humans of a coronal mass ejection is on our satellites, which can be seriously damaged. Power

cuts on Earth can also take place.

Although we may now understand the basics of the Sun, we remain unable to reliably predict everything

about it. There is much still to understand and learn about it, and it seems the more intensely it is

studied, the more questions there are to answer!

The Exploration of Mars

A In 1877, Giovanni Schiaparelli, an Italian astronomer, made drawings and

maps of the Martian surface that suggested strange features. The images from telescopes at this time

were not as sharp as today. Schiaparelli said he could see a network of lines or canali. In 1894, an

American astronomer, Percival Lowell, made a series of observations of Mars from his own observatory at

Flagstaff, Arizona, USA. Lowell was convinced a great network of canals had been dug to irrigate crops

for the Martian race! He suggested that each canal had fertile vegetation on either side, making them

noticeable from Earth. Drawings and globes he made show a network of canals and oases all over the

planet.

B The idea that there was intelligent life on Mars gained strength in the

late 19th century. In 1898, H.G. Wells wrote a science fiction classic, The War of the Worlds about an

invading force of Martians who try to conquer Earth. They use highly advanced technology (advanced for

1898) to crush human resistance in their path. In 1917, Edgar Rice Burroughs wrote the first in a series

of 11 novels about Mars. Strange beings and rampaging Martian monsters gripped the public's imagination.

A radio broadcast by Orson Welles on Halloween night in 1938 of The War of the Worlds caused widespread

panic across America. People ran into the streets in their pyjamas-millions believed the dramatic

reports of a Martian invasion.

C Probes are very important to our understanding of other planets. Much of

our recent knowledge comes from these robotic missions into space. The first images sent back from Mars

came from Mariner 4 in July 1965. They showed a cratered and barren landscape, more like the surface of

our moon than Earth. In 1969, Mariners 6 and 7 were launched and took 200 photographs of Mars's southern

hemisphere and pole on fly-by missions. But these showed little more information. In 1971, Mariner 9's

mission was to orbit the planet every 12 hours. In 1975, The USA sent two Viking probes to the planet,

each with a lander and an orbiter. The Landers had sampler arms to scoop up Maritain rocks and did

experiments to try and find signs of life. Although no life was found, they sent back the first colour

pictures of the planet's surface and atmosphere from pivoting cameras.

D The Martian meteorite found in Earth aroused doubts to the above analysis.

ALH84001 meteorite was discovered in December 1984 in Antarctica, by members of the ANSMET project; The

sample was ejected from Mars about 17 million years ago and spent 11,000 years in or on the Antarctic

ice sheets. Composition analysis by NASA revealed a kind of magnetite that on Earth, is only found in

association with certain microorganisms. Some structures resembling the mineralized casts of terrestrial

bacteria and their appendages fibrils of by-products occur in the rims of carbonate globules and

pre-terrestrial aqueous alteration regions. The size and shape of the objects are consistent with

Earthly fossilized nanobacteria, but the existence of nanobacteria itself is still controversial.

E In 1965, the Mariner 4 probe discovered that Mars had no global magnetic

field that would protect the planet from potentially life-threatening cosmic radiation and solar

radiation; observations made in the late 1990s by the Mars Global Surveyor confirmed this discovery.

Scientists speculate that the lack of magnetic shielding helped the solar wind blow away much of Mars's

atmosphere over the course of several billion years. After mapping cosmic radiation levels at various

depths on Mars, researchers have concluded that any life within the first several meters of the planet's

surface would be killed by lethal doses of cosmic radiation. In 2007, it was calculated that DNA and RNA

damage by cosmic radiation would limit life on Mars to depths greater than 7.5 metres below the planet's

surface. Therefore, the best potential locations for discovering life on Mars may be at subsurface

environments that have not been studied yet. The disappearance of the magnetic field may be played a

significant role in the process of Martian climate change. According to the valuation of the scientists,

the climate of Mars gradually transits from warm and wet to cold and dry after magnetic field vanished.

F NASA's recent missions have focused on another question: whether Mars held

lakes or oceans of liquid water on its surface in the ancient past. Scientists have found hematite, a

mineral that forms in the presence of water. Thus, the mission of the Mars Exploration Rovers of 2004

was not to look for present or past life, but for evidence of liquid water on the surface of Mars in the

planet's ancient past. Liquid water, necessary for Earth life and for metabolism as generally conducted

by species on Earth, cannot exist on the surface of Mars under its present low atmospheric pressure and

temperature, except at the lowest shaded elevations for short periods and liquid water does not appear

at the surface itself. In March 2004, NASA announced that its rover Opportunity had discovered evidence

that Mars was, in the ancient past, a wet planet. This had raised hopes that evidence of past life might

be found on the planet today. ESA confirmed that the Mars Express orbiter had directly detected huge

reserves of water ice at Mars' south pole in January 2004.

G Researchers from the Center of Astrobiology (Spain) and the Catholic

University of the North in Chile have found an 'oasis' of microorganisms two meters below the surface of

the Atacama Desert, SOLID, a detector for signs of life which could be used in environments similar to

subsoil on Mars. "We have named it a 'microbial oasis' because we found microorganisms developing in a

habitat that was rich in rock salt and other highly hygroscopic compounds that absorb water" explained

Victor Parro, a researcher from the Center of Astrobiology in Spain. "If there are similar microbes on

Mars or remains in similar conditions to the ones we have found in the Atacama, we could detect them

with instruments like SOLID" Parro highlighted.

H Even more intriguing, however, is the alternative scenario by Spanish

scientists: If those samples could be found to that use DNA, as Earthly life does, as their genetic

code. It is extremely unlikely that such a highly specialised, complex molecule like DNA could have

evolved separately on the two planets, indicating that there must be a common origin for Martian and

Earthly life. Life-based on DNA first appeared on Mars and then spread to Earth, where it then evolved

into the myriad forms of plants and creatures that exist today. If this was found to be the case, we

would have to face the logical conclusion: we are all Martian. If not, we would continue to search the

life of signs.